1889-1912 |

|

|

Contributed by Jerry Blanchard, 7-30-10 |

|

|

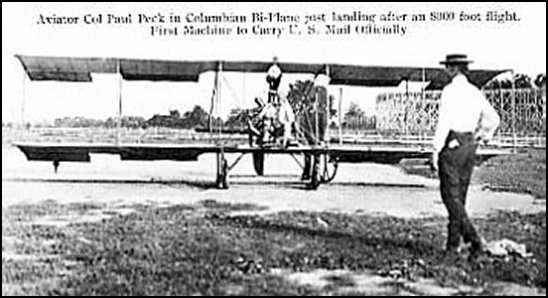

just landing after an 8,000 foot flight. First Machine to Carry U. S. Mail Officially Photo Courtesy of AeroFiles |

by Maurice L Marotte III 1-11-05 I have been collecting old photos and postcards,etc. for about 42 years.I can tell you some things about Paul Peck. On September 23 rd, 1911, Paul came to Chambersburg by the Cumberland Valley Railroad and his plane was on several flatcars in pieces and upon arriving in Chambersburg his crew assembled the airplane. My grandfather, Maurice L Marotte Sr., was on hand for the whole event and Paul let my grandfather sit on the old crate that was used for the seat. When Paul took off to fly over Chambersburg,Pa, my grandfather was holding the one side of the wing while taking off so the wing would not tip into the uneven ground. Paul and his plane was the first air plane to fly over Chambersburg on Sept 23rd,1911. There are only approximately 7 known real photo postcards done that day and are identified by the photographer Beidel.These are very rare and I have seen many people from all over the world looking for these real photo postcards. The last one I saw 2 years ago sold at auction for $1100.00 to one of the DuPonts. There were about 15 bidders on the postcard. It was stated that there were people from various parts of the country trying to buy this rare piece of history. I do know where there is a real photo postcard of Pauls airplane flying over Chambersburg, Pa. Do you have any interest in this? Please let me know Thanks Mike |

|

|

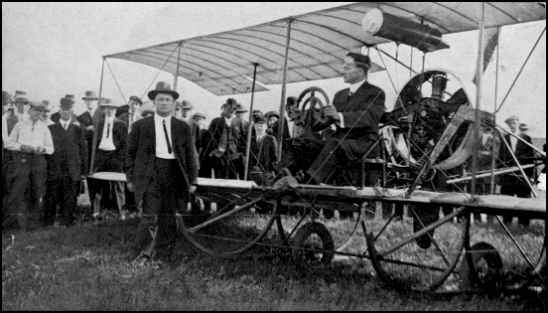

Contributed by Jerry Blanchard, 7-30-10 Here is a period postcard view of Paul Peck taken at Coney Island Park Aviation Meet outside Cincinatti OH on July 19-20-21-1912. Pictured here with H L Tucker who was his manager with Berger Aviation. It is a little known fact that Peck flew the mail during the first air mail event at Garden City Long Island NY in September 1911. This was his second air mail flight and it was the first where a Post Office was specifically established for the carring of mail. Tucker charged an additional $.10 for the privelage of it being carried by Paul Peck. This is one of the scarcest Pioneer Air Mail as few examples have been located. Jerry |

|

Birdman of West Virginia West Virginia's trailblazing first pilot remains largely unrecognized. Until now. Sunday June 15, 2003 By Sandy Wells STAFF WRITER A storm loomed. Dark, churning clouds encroached rapidly from the northeast. Tree limbs swayed under the force of the rushing gale. Paul Peck climbed into his flying machine, jaw clenched, eyes staring straight ahead, determined to complete the first flight over West Virginia's downtown Capitol. The round-trip journey, starting from the South Charleston ball field, would cover nearly six miles." Just as the plane scooted forward, the storm hit. Lightning shot from the clouds. Thunder deadened the sound of the whirring, sputtering engine. Ferocious wind whipped the wings. A Gazette reporter watched with growing concern: "It looked as though all the elements had combined to defeat the object of this white-winged invention of man and to wreak their vengeance upon the aviator who would dare to pit his skill and daring against their fury." It was June 26, 1912, the second day of a three-day aviation meet. Nearly 5,000 people turned out for their first look at the wonders of flight. The warm, sunny morning offered no hint of the storm that raged through the valley that afternoon. Bad weather never bothered Paul Peck. The reporter saw resolve in his demeanor. "There was in the countenance of the former Charleston boy, as he sat amid the network of steel wire and faced the darkened horizon, that said more plainly than words that he would achieve his expressed purpose of encircling the dome of his state's capital." Fearlessly, Peck plowed his way through heavy wind toward Charleston, flying as high as 2,000 feet. "The game little flyer had to fight for every inch he gained against the wind," the Gazette reported. Somehow, Peck stayed the course. Just past the dome, he made a sudden, sensational swing to the east and north. A perfect circle. Returning ahead of the gale, traveling at 75 miles an hour, he covered the three miles back to the ball field in 90 seconds. Amazing! He landed deftly in an open space near the ball field. The crowd cheered. His journey took 11 minutes and 30 seconds. "Nature had done her worst," the paper reported. "Man had done his best. And man had won." At least for now. Col. Paul Peck - his rank was bestowed by the governor - had a reputation for brilliance in storms. Flying at Long Island, he set a world duration record amid lightning and hail. Two months after his celebrated performance here, he represented the United States in the International Gordon Bennett Trophy Race at Chicago. A storm erupted. He died, fittingly, in midair. He was 23. Forgotten hero The Wright brothers. Lindbergh. Earhart. Those names we know. Yet 100 years after the Wrights' inaugural flight, and 91 years after the midair catastrophe that killed Paul Peck, who remembers him? Born in Ansted, the son of Lon and Alice Peck of Lewisburg, he grew up mostly in Hinton where his father worked as a railroad agent. He also lived for a time in Philadelphia and in Charleston where two brothers settled. Intrigued by machinery as a boy, he gravitated to the new automobiles and loved tinkering with their motors. As a young man, he worked as a chauffeur in Washington for financier Isaac T. Mann, a millionaire from Bramwell. In 1911, two days after his 22nd birthday, he began flight lessons. The same year, he married a woman from Washington, D.C., where they made their home. Within a year, she died. Five months later, he lay beside her at Union Cemetery in Rockville, Md. He left behind a year-old son who later died at the age of 7. Peck's name pops up in aviation annals, mentioned in the gap between Kitty Hawk and the astounding aeronautical advances forged by two world wars. But in his home state, the achievements of West Virginia's daring, trailblazing birdman remain largely unrecognized. He was the state's first pilot, the 57th licensed by the International Aeronautics Federation. He learned to fly in seven days. Within two weeks, he captured a world flight record. He probably was the first to fly in West Virginia. Historians believe he piloted the first plane to land in Raleigh County and that the flight occurred before 1912. He was the first to fly over the U.S. Capitol, setting a speed record of 24 miles in 25 minutes. He set an endurance record, flying over Boston for four hours, 23 minutes and 15 seconds. He also held a record for landing accuracy. When the nation's first military aviation school opened at College Park, Md., in 1911, he was one of the instructors. Rare postcards coveted by collectors commemorate his role in the first U.S. airmail flights. A huge photo displayed in the Aviation Museum in College Park shows him with a Rex Smith plane. The museum salutes him as a test pilot for the Rex Smith Aeroplane Co., an airplane designer and well-known exhibition flier. In West Virginia, a single plaque in the lobby of the Greenbrier County Airport memorializes his contribution to flight. People do stop and read it, said airport manager Jerry O'Sullivan. "There's not a lot to do in terminals." Peck's last descendants presented the plaque to the airport in 1979. Col. John Gwinn, airport manager at the time of the presentation, commended the family for choosing the airport location: "Peck's importance to aviation history is not realized by many West Virginians," Gwinn said in a 1979 newspaper article. "This man was flying seven years after the Wright brothers' first successful flight. He was flying when Lindbergh was only 9 years old." He remained one of the rare people in America working to perfect flight after the Wright brothers' breakthrough, O'Sullivan said. "The French picked it up and most of the development took place in France. The plane was just an oddity here. It wasn't until after World War I that we started to get into the game. It's very important that he didn't drop the ball." The show of shows Valley residents cheered heartily for their homegrown hero during the 1912 air show at the South Charleston ball field. They'd read about the event for days in The Charleston Gazette. Using the flowery prose of that era, the paper promised spectators much excitement: "The air will be full of these famous aeroplanes, whirling, gliding, dipping, sailing, tearing through the air at a mile a minute, their engines popping a fusillade of explosion and the deafening noise of their powerful motors heard for a distance of miles." To reach the ball field (the eventual site of Union Carbide), spectators could take a streetcar or a 10-cent ride aboard the steamer Valley Bell. The boat made two trips from the foot of Summers Street, first at 1:15 and again at 2:15, just in time for the 2:20 show. Most arrived early, eager for a close look at the newfangled flying machines. The winged contraptions attracted the kind of curiosity we'd reserve today for a flying saucer. "It didn't seem possible that those 1,100 pound monsters could rise into the air like a bird and fly just as well as a bird," the Gazette reported. A farmer in town for the spectacle just shook his head. "T'aint in water," he said. "I don't understand how that there thing can fly. But the paper says so, and I'm going to see if it can be done." He watched the first flight, dumbstruck. "It do beat all how they do things nowadays," he said finally. The Gazette deemed the opening program "the greatest entertainment ever witnessed by the people of Charleston and Kanawha County." Later, the reporter found Peck at the cashier's desk in the office of the Kanawha Hotel. A young man in spectacles, he was cramming greenbacks into an envelope to deposit for the American Aviation Co. The reporter asked how he felt way up in the air. "Well, a young lady once asked me that question, and I asked how she felt when she received her first proposal of marriage," Peck replied. "She said she couldn't tell me. And that's the way it is with me." Peck flew the plane he designed and built, a push-type Columbian biplane with a rotary motor, the one he used to set a world duration record. The plane had been on exhibit at the Barrett & Shipley department store at Quarrier and Hale streets. He was proud of it. "He talks little about himself and a lot about his machine," the Gazette reported. Two other pilots in the show, Oscar Brindley and Eugene Heth, flew the famous biplanes contrived by Wilbur Wright. The Wrights insisted on the superiority of their cylinder engine and double propeller model that could fly 40 miles an hour at 600 to 700 revolutions a minute. Pilots controlled the Wright plane with levers. Peck used a steering wheel to direct his Columbian biplane. Peck's 50-horsepower Gyro rotary engine and single propeller plane flew 70 miles an hour on 1,200 to 1,500 revolutions a minute. During the three-day spectacle, his plane flew faster and earned praise from spectators for the most graceful descents and landings. "The landings are the features that the spectators appear to enjoy most," the newspaper noted. "To see the great air birds sweep down and do a spiral glide onto the earth, the penetrating whirr of the revolving shafts sounding like the angry hum of a giant wasp - and then rush along the ground with the speed of an auto and the aspect of a winged prehistoric monster - that is a sight that banishes boredom and gives a thrill to the most sluggish pulse." But Peck's airborne antics also kept pulses racing. He mesmerized the crowd with his perilous "ocean roll," a maneuver that demanded perfect control and balance. The series of short dips and upflights required the engine to shut off before each dip and spark up again for the ascent. A legacy in death Always, the Grim Reaper waited in the wings. But with every takeoff and landing, with every spiral and ocean roll, the fearless pilots defied him. The Gazette reporter attributed their bravery to fatalism. During their visit here, he watched Peck and the other two pilots perusing pictures of biplanes in action. One photo captured an aviator on his final, fatal trip. "Their remarks gave evidence of that fatalism, as it is called, that exists in all bird men - a feeling that what must be will be. Feeling so, they have no nervousness when taking their lofty flights." At the Chicago exhibition two months later, Peck started his steep spiral, ignoring the sudden storm. Nobody knows why the engine came loose. The plane had to be shipped by train from Washington to Charleston to Chicago. Maybe it happened along the way. On the pusher model plane he preferred, air pushing from the propeller powered an engine behind the cockpit. The loosened motor cut through the pilot's seat with its whirling propeller. His plane disintegrated in the air. Even in death, Paul Peck made history. His funeral was Washington's first automobile funeral. The procession featured a motor hearse, a motor wagon laden with elaborate floral pieces and about 30 other automobiles. In a story previewing the South Charleston show, a Gazette writer praised the bravery of those who risked their lives for progress. It could be Peck's epitaph: "The science takes its toll at an average of about one a week, of some crushed aviator consigned to his grave. But it is fortunate for the future of aviation that there are young men - and women too - of such daring as to defy the dangers of it." Ninety-one years ago, the reporter predicted a time when men and women would soar through the skies with as little concern as traveling to France on an ocean liner: "Day after day will come practical information, through discovery of features tending to eventual safety, until at last there will be no more danger in travel through the air than over the land or the water." To contact staff writer Sandy Wells, use e-mail or call 348- 5173. Peck's record Paul Peck, who was West Virginia's first pilot, had many other flight-related achievements: He learned to fly in seven days. Within two weeks, he captured a world flight record. He was the first to fly over the U.S. Capitol. He set an endurance record, flying over Boston for nearly four and a half hours. When the nation's first military aviation school opened in 1911, he was an instructor. Coveted rare postcards commemorate his role as one of the first U.S. airmail pilots. Write a letter to the editor Reprinted by permission |

|

from the Early Birds of Aviation CHIRP June, 1937 - Number 20 |

|

|

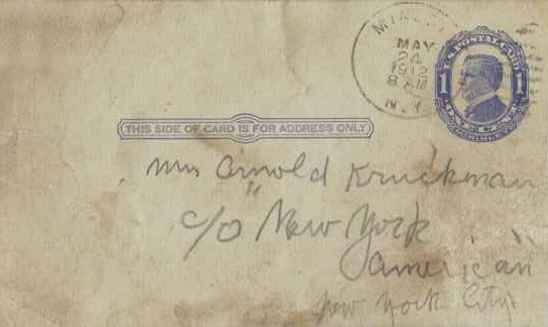

from Michael Terzano, 4-30-10 This is probably not of much historical interest to you but here goes anyway: When I was a youngster in the mid 1960's (I'm 57 now), I lived in a town named Hazlet in Monmouth County N.J. Hazlet was not the name of the area, however, back in the early days of the 20th century. I'm not sure what is was called then. We used to play in an old derelict abandoned house on Middle Road in the town. It may have once belonged to the Hendrickson family who were prominent there, way-back-when. There was lots of old junk in the house like newspapers, magazines etc. I collected stamps in those days so my eye caught sight of an old one cent postcard on the floor so I picked it up for my collection. It is postdated May 24, 1912, and addressed to "Mr. Arnold Kruckman, c/o New York American, New York City". The reverse reads: "Am having an aerial joy ride with Paul Peck, 1,500 ft. above Nassau Boulevard. Donald Phillips

Well, that's my story. Just wanted to share it with you. Sincerely,. Michael V. Terzano Tinton Falls, NJ 07724 Subsequent to my original e-mail to you I did some more investigating. My boyhood town of Hazlet was known as Raritan Township until 1967. And the abandoned house where I found the postcard was indeed once owned/occupied by members of the Hendrickson family in the late 19th/early 20th century. They were a large farming family who were instrumental in settling the area from back in the 1700's and a cursory web search of the Hendricksons showed a number of Phillips' named as family members in the 1880's, possibly by marriage, or cousins etc. There was a Phillips Mill in the area back in the 1800's so it would appear they too were a family of some significance in the area in the old days. I haven't found any reference yet to Donald Phillips per se, but I'm on the quest. I have posted a Donald Phillips query on the Monmouth County, NJ Forum of genealogy.com, so hopefully some descendent may respond with info as to who he was and how he knew Paul Peck, Kruckman et al.. I will keep you apprised of anything I learn that may shed light on Phillips' relation to Peck and/or his interest in early aviation. Thank you for getting back to me and taking an interest in my little story. My wife is a computer search wizard and is assisting in the investigation along with our two rescued black cats Midnight and Malibu who are always involved in all family activities. Yours Very Truly, Mike Terzano |

|

Contributed by Michael Terzano 11-30-12 Dear Ralph, Pursuant to my earlier correspondence to you concerning the old postcard I found as a child in an old house in Monmouth County, NJ which told of this unknown gentlemen's "aerial joyride" with Paul Peck, there has been a new development. As you know, back in 2010 I posted a query about the identity of Mr. Phillips on Geneaology.com, with all the relevant info regarding the postcard, Paul Peck, Arnold Kruckman etc. Recently, in early Nov. 2012 I finally received a response from a Susan Dewing who said Donald Phillips was her grandfather, and asking what information was I looking for. Naturally I enthusiastically responded, telling my story and of my interest in exactly who he was and how he was acquainted with Paul Peck and Kruckman. I gave her my mailing address, e-address and telephone number urging her to contact me anytime so we could converse about this fascinating historical topic. But alas, no further communication from her as of y et. I am presuming that she must be at least in her 70's if Phillips (who knew Peck in 1912) was her grandfather. I guess I'll just have to be patient and hope she'll contact me sooner or later. I'll certainly keep you posted as to anything I might learn about Peck, etc. Best Regards, Michael Terzano Tinton Falls, NJ |

|

|

|

If time permits, be sure to visit the many other sections such as Field of Firsts, Founding, Early Civilian Aviation, Army Signal Corps Aviation School, etc. You can access the page by clicking on the title above. |

|

|

|

Machine Falls with Paul Peck, at Chacago, the Heavy Engine Crushing Through Wreckage upon Hapless Airman Knoxville Daily Journal and Tribune Knoxville, Tennessee: September 12, 1912 Transcribed by Bob Davis - 6-9-04 A gusty wind blew at Cicero field all day and Director Andrew Drew posted the customary warning to aviators against going up. Peck, believing his small biplane would be fast enough to carry him through the choppy wind, went into the air in spite of the caution. At about eight hundred feet altitude, he started to come down in a spiral glide. Because of the unusually small span of his machine, Peck got into too steep a spiral, his aeroplane slid in toward the center of the vortex, and he could not bring it back. [We know today that you must first roll with the ailerons and rudder to level the wings before you pull back on the stick to pull the nose up with the elevator.] His real difficulty did not become apparent till he was within 200 feet of the ground. He would have escaped with minor injuries, Director Drew and his technical committee declared, had it not been for the fact that the heavy engine, crashing through the framework, with its gasoline tank and iron fittings, struck Peck in the neck and across the legs. He died an hour later in St. Anthony de Padua hospital. Peck was American licensed aviator No. 57 and [he] had developed a monoplane and the biplane in which he was killed. The biplane was of only 26 feet span, headless [no elevator in front] and equipped with a Gyro motor. He was about twenty-four years old and was making a trial flight preparatory for the international aviation meet here tomorrow. Twenty-four American and foreign aviators will meet tomorrow on the Cicero flying field to contest for prizes aggregating $24,000 offered by the Aero Club of Illinois. The aviation meeting will continue ten days. Among the entrants are: Maurice Prevost, George Mestach, J. R. Montero, C. L. McGrath and Mariel Tourbler, who will fly French machines; Guiseppe Callucci, Italian military aviator; Ignats Seminouk, representing Poland; A. C. Beech representing England, and Max Lille de Lloyd Thompson, Farnum T. Fish, Glenn H. Martin, Andrew Drew, C. M. Vought, Archie Freeman, Beckwith Havens, Howard Gill, Otto W. Brodie and Anthony Janus, representing America. |

|

Knoxville Daily Journal and Tribune Knoxville, Tennessee: September 12, 1912 Transcribed by Bob Davis - 6-9-04 Peck was about twenty-three years old. While he made his home in Washington his parents live in West Virginia. His young wife died here last April after a transfusion of blood from her husband had been made in an attempt to save her life. To officers of the United States army aviation corps, Peck's death came as a shock as he was known to have been a very careful aviator. |

|

If you have any more information on this pioneer aviator, please contact me. E-mail to Ralph Cooper Back

|