|

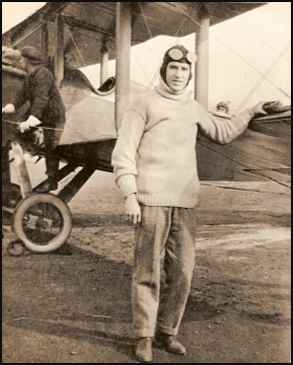

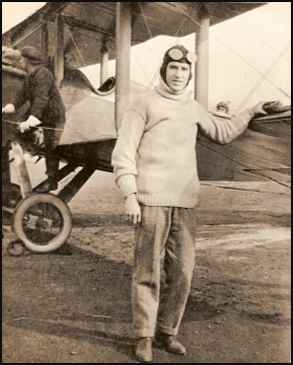

by Bernard L. Whelan (Around May, 1913) Courtesy of Mary Anne Whelan |

|

I was still working at "Thomas" when my father gave me his check for $250.00 to start flight

training at Simms Station. Incidentally I still have that cancelled check along with the signed training agreement. The initial payment

covered only a little more than 4 hours air time training. I soloed within that amount of air time but subsequently spent an equivalent

amount for additional dual instruction and some solo flying. After signing up at The Wright Company, I told Harry Matthews, brother of

the President and principal owner of Thomas Manufacturing Company, what I was intending to do. He apparently told his brother and

while riding up to the office section on the elevator one morning, M.H. Matthews was also aboard. He mentioned that he heard I was

going to give up my job and take up flying. I said, "Yes, I want to learn to fly." He said, "Well, I think you are a damned fool." The Wright Company plant was as I recall on Coleman Street, on the west side of Dayton. The street names have been changed to some extent in that area but the two or three buildings that constituted the world's first production aircraft plant are still there and readily identifiable due to their distinctive front elevations. They were acquired and occupied by Inland Manufacturing Company, a division of General Motors a few years after WWI. Somewhere on them there should be a bronze tablet marking their historic significance. At the time I was enrolled for flying instruction, Frank Russell, a man I grew to admire and respect was General manager. Looking back he reminded me somewhat of Mr. Fred Rentschler, principal organizer of United Aircraft Corporation. A large man, he was a very able executive and personable - a man you could talk to. Years later he became part of the Curtiss-Wright organization. Each day I would leave our house at 312 Hughes Street, later renamed Stone Mill Road, and take the street car to the Wright Company plant. I was thrilled and amazed at what I saw there, not realizing until then that aviation was well along the road toward becoming a real industry. Model B's and C's were under construction and their 40 and 70 horsepower engines were undergoing test on test stands driving flat test "clubs" to absorb engine power. One of the first surprises I had was to find, in a little used section of the plant what might be called a static trainer. It consisted of an old disused Model "B", cradled so that it could oscillate laterally, an electric motor driving a cam which continuously changed the pattern of lateral movement. When the student moved the combination wing warp (aileron) and rudder lever correctly the wings would be brought back to a level position. Students were directed to practice on that device until the movemments of the controls to correct lateral imbalance became instinctive. Then next step was to go to Simms Station where I met Oscar Brindley, the Wright brothers flight instructor at that time. I instantly liked Brindley. He was of sober countenance but could smile easily and did so frequently. There were six other students there at the time. Flight instruction was usually given in the afternoon. If I happened to be at the factory in the morning Brindley would give me a ride out to Simms in the company car which I believe was an "Oakland'. Otherwise I would take the electric interurban which ran between Dayton, Springfield and Columbus, and at that time made Simms Satation an official stop. Instruction would start with the students running a detailed inspection of the Model "B" under Brindley's direction, concentrating on the controls and propellers and their chain drive mechanism: (It was a propeller failure which led to the accident at Fort Myer in which Lieutenant Selfridge was killed and Orville Wright seriously injured.) Then they would be given air time in turn. After I had a few dual control flights with Brindley he counseled me not to be in a hurry to use up the air time paid for, that it would be to my advantage to string it out as much as reasonably possible and spend the in-between time listening to the ground instructions given others and learning more about the mechanics of the plane. This turned out to be good advice and, as he pointed out it was feasible for me since I was living at home in Dayton while others had to consider the expense of hotel or boarding house living. They had some cots and blankets in the hangar at Simms and occasionally we would spend a night there and get our dinner and breakfast a few hundred yards away at the Beards' who ran the farm for the Huffmans. And what meals they were! I will always remember those more than substantial breakfasts. Then when flying started we would first have to chase a few cows and a horse or two belonging to the Huffman farm out of the way. One horse was especially domesticated. I have a picture somewhere in the collection showing him taking a cracker from Roderick Wright's (no relation) mouth. There was seemingly no identifiable trend pointing to the type of man who enrolled for flight instruction. In one group there was an Indiana farmer, Roderick Wright; a cultured man from Boston, Maurice T. Shermerhorn; a postmaster from Colorado, W. Bowerson; a navy enlisted man taking time off pending re-enlistment, A. Bressman, and Maurice Priest and John Bixler of whose earlier interests or locals I have no knowledge. However, they all had one common denominator, an intense desire to learn to fly and generally speaking, follow aviation as a career. Even so "circumstances alter cases" and to the best of my knowledge based on aviation publications and personal contacts only one or two of them besides myself did any considerable amount of flying. Looking back after all these, oh so many years, I just say that the summer of 1913 spent learning to fly at Simms Station was one of the happiest periods of my life. Flying was so new and original and, if you will, romantic in a sense. The Wright "B" was as controllable as any plane I piloted in subsequent years. Very light pressure was required for response in each of the three elements of control - vertical, horizontal and directional, and flying in itself gave one a feeling of exhiliration, especially in a Wright "B" of that vintage where you sat entirely exposed to the elements on a seat near the leading edge of the wing. A surprise when you had your first flight was the fact that there was no feeling of height, something hard to understand except that you were in or on a moving vehicle and not stationary above anything reflecting a vertical dimension. That feeling of height in an airplane is present only if one is flying close to and directly above something similar to a vertical mountain wall or even a very high building and looking down. An unexpected aerodynamic characteristic related to the function of the rudder. Even today most people unfamiliar with flight controls would say the rudder of an airplane is a devise for steering directionally. This is true only on the ground in taxiing, and for minor directional corrections in level flight. The principal function of a rudder on an airplane is as a balancing device to offset or prevent "side-slipping" or "skidding" in banked turns either of which can lead to loss of control and an accident. Its use is coordinated with the degree of banking and in steeply banked turns the rudder gradually assumes the function of the elevator and vice versa. Brindley gave us a smattering of such aerodynamic fundamentals and frequently repeated the counsel - "DON'T STALL". To stall an airplane is to lose flying speed and therefore its sustaining lift, which is generally followed by, first, a pancaking effect and then a dive in which case, unless you have room to recover, sends you on your way to meet the Saints. Planes of a later vintage had a degree of longitudinal stability which automatically enabled them to go into a glide in event of loss of power but even so the records are full of fatal accidents due to a stall, generally near the ground. Brindley used to say, "Never take off without keeping in mind what you intend to do in the event of motor failure before you have gained a reasonable altitude", but sometimes there is no place to go, although I really believe his counsel along that line perhaps saved my life on one occasion to be explained later. Toward the middle of the summer of 1913 I had accumulated about eight to ten hours of flying, having added about an equivalent amount ot the $250.00 my father had given me for the first lessons up to the time I received the F.A.I. license number 247. Then an incident occurred which had all the earmarks of an opportunity to earn a living through flying. Telling of it here will introduce an unforgettable character, one of many that will come to mind as memory retraces the bygone years. At that time Brindley was not only the instructor at the Wright School, but was also their demonstrator for planes sold to the government. In between times he also had been flying exhibition dates for one William Jim Gabriel. Gabriel had previously been the propriator of a side show, in his parlance a "Three in one show" which accompanied the best known circuses that travelled from town to town. He had given up that circus connection and somehow acquired a Model "B" Wright and booked exhibition dates, and prior to Brindley had employed Leonard W. Bonney as his pilot. Bonney had F.A.I. (Federation Aeronautic International) license number 47, just following Brindley's license number 46. He had been an able pilot, but had left Gabriel for some better connection. Now Brindley was giving up the exhibition work and had recommended me to Gabriel. I shall never forget my first meeting with him. He had phoned me at home saying he wanted to talk to me about flying for him and that he had a date soon coming up for a two day exhibition at Medina, Ohio. He asked me to meet him at the Phillips House Hotel for a drink and to talk things over. At that time the Phillips House Was perhaps Dayton's most popular hotel. There was a lobby and bar downstairs and a presentable dining room on the second floor. It was there you could go following a stage play at the Victoria Theater or from a movie and get for free a late supper consisting of a generous slice of good roast beef and a large serving of baked beans or cole slaw. You were expected to give the server at the steam table a dime - ten cents - not as payment but as a tip for his serving you. Then you would take your plate to the bar and order your beer. In the light of today's practices and prices it sounds unbelievable but it was true, they gave the food away as an inducement to sell the beer. Full course dinners upstairs were about fifty or seventy-five cents. Meeting Gabriel at the Phillips House bar he ordered something like a Manhattan but I think I settled for a short beer. Up to that time I never knew what a cocktail was, but we always had beer at our house. Then he proceeded to tell me about his problem with Leonard Bonney who had been flying for him. Although he was from New York he spoke with something akin to a southern drawl. He said, "When I hired Bonney he didn't have enough to buy a bean sandwich. I put him on my payroll and fed him, and got the wrinkles out of his belly and then he leaves me - and what for? For a few paltry dollars!" Gabriel was by no means typical of the man usually engaged in booking exhibition flights, but had bought a Model "B" and proceeded to book dates using Brindley as pilot after Bonney left him. Now Brindley was too busy with training and military demonstrations to continue along that line, but he would fly the first day of a two or three day date at Medina, Ohio "to break me in", and I would do the flying from then on. I was to be paid $25.00 a week and expenses while on the road and $50.00 a day for every day I flew. I felt sure I was going to get rich. There being no such thing as regular cross country flying those days the plane was shipped to Medina, Ohio in an end-door box car partly disassembled, and then reassembled at the fair grounds in Medina, Brindley and I doing most of that work, we going by train along with Gabriel. The most prominent man in Medina was Mr. A.I. Root, who could be rated a scientist and who engaged in bee culture and the sale of honey and bees. It was a nation-wide business. He had happened to have driven his electric automobile from Medina to Xenia, Ohio, (the home of my maternal grandparents), a 175 mile trip, which was a feat in itself for those days. having heard about the Wrights and being nearby he decided to visit them at Simms Station and by good fortune arrived there on September 24, 1904 - the day they had completed the first circular flight of an airplane. He later wrote an eyewitness account of what he had seen in the January 1, 1905 issue of his magazine "Gleaning in Bee Culture" and sent a copy to the editor of the Scientific American, accompanied by a letter to the editor telling him he was free to print the article. It was ignored. He continued to print articles about the Wrights in his magazine including one in December, 1905 calling attention to the fact that a great number of long flights had been made in the previous season including one of 24 miles in 38 minutes, probably the first publication of that event in the United States. Mr. Root was the man at the head of the Chamber of Commerce of Medina, Ohio who sponsored Gabriel's exhibition date. While all this led to friendly association between Root and the Wrights, except for selling Gabriel a Model "B" they, the Wrights, had no connection with the exhibition date. The plane had been stored in a tent on the fairgrounds. Brindley was preparing for the flight and had promised to take me along for my experience. The Chamber of Commerce had charged fifty cents each for entrance to the grounds and Gabriel was collection another ten or twenty-five cents for spectators to enter the tent and walk around the machine in single file for a close-up view of the Model "B". Some would get in line again and come in a second time. It was a very hot July day and before a flight could be attempted a serious thunderstorm accompanied by very high winds suddenly developed over Medina and the fair grounds. The crowd, perhaps two thousand, rushed for cover, filling the tent and many rushing for the protection of the trees bordering the south side of the fair ground race track. There, two men, both farmers, were struck by lightning and killed. Before we had even heard about that tragedy one end of the tent billowed in the high wind, literally pulling a large tent pole out of the ground which fell against the rear structure of the plane seriously damaging the rudder and elevator and part of their supporting outriggers. It was out of the question to fly or even to make repairs to lfy the following day. The crowd gradually filed out and headed for their homes and Brindley caught a train from Cleveland to Washington, where he was to handle something for the Wright Company. As you can well imagine dinner that evening was a dolorous affair. No one had much to say. Gabriel had a drink or two before dinner and remained very glum, but after dinner he occupied a small table along one side of the hotel lobby and really settled into serious drinking in an apparent attempt to drown his woes. Then he began to talk to himself but loud enough so that I coudl hear. "This aviation business is no damn good! It's just costing me a lot of money. I should go back to the "Three In One Show". There's your wild man, costs you twelve bucks a week, and your crazy woman, ten or twelve bucks a week, and your giant and dwarf or your snake charmer ---. The following morning after breakfast Gabriel seemed to be getting the better of his well deserved hangover and also had a sudden inspiration. He jumped up suddenly from the table and said, "C'mon kid, we're going down and see that bee man". We walked down the main street of Medina and turned left on the street where Mr. Root lived near his bee and honey factory. To our surprise Mr. Root was coming down the dusty road in his electric automobile. Gabriel walked out to the center of the street and raised up his arms in a gesture requesting him to stop. I followed closely behind. Then introducing himself, although Mr. Root already knew him from the day before, he launched into a plea for at least reimbursement of expenses in connection with the aborted exhibition flights. Gabriel was cunningly clever in his sales approach. He knew Mr. Root had the reputation of being religiously inclined and that he also had a firendly acquaintanceship with Orville Wright. "Mr. Root," he said, "it was the hand of God, and act of Providence. I would not have let the kid here fly after those poor people were struck down by lightning for all the money in the world." Then he would add, "I don't know what Orville will say; I just don't know what Orville will say", as he shook his head dolefully. Of course, as explained earlier, Orville and/or The Wright Company had absolutely nothing to do with booking the exhibition although they would obviously have liked to see it go off well. In a sense Gabriel had a case against the Chamber of Commerce of Medina since they had charged fifty cents each for people to enter the fairgrounds where they could actually see an airplane fly. They obviously had no practical way of refunding that to each and every person. Likewise, Gabriel had received some revenue in the fee he charged for people to walk around the airplane in the tent for a close-up view, but that came nowhere near offsetting all his expenses. I never knew exactly but think he finally received some $500. to $750. for bringing the airplane there even though it was not flown on that occasion. The following week the airplane was repaired with the assistance of a mechanic from the Wright factory who brought along the required material, and was then moved to a farm near the edge of Cleveland. Gabriel had been working on a contract to fly several times a week over a Cleveland amusement park, "Luna Park", I believe. In the meantime I test flew the plane from the farm on two occasions but staying away from the amusement park. After the first flight there were possibly more people at the farm where the plane was kept than in Luna Park, but Gabriel never succeeded in closing a contract with the Luna Park people. In low spirits he decided to return the plane to Dayton, he and I and the factory mechanic also returning by train. That was the last time I ever saw Gabriel, on that particular plane and must assume that he sold it. He had paid me something for making the test flights after the Medina accident, and all my expenses away from Dayton. Several months later I had a letter from him from New York inquiring if he owed me any money. He did not menmtion what he had done with the plane. And that ended my first but abortive attempt to earn a living from flying, although by then I was more than ever convinced that the science and art of aviation wold develop rapidly and present many worhtwhile opportunities. The Wright invention applicable to the field of Transportation was fundamentally too sound to remain static. |

|