1885-1968 |

|

|

Waldorf-Astoria Hotel, New York, 1910 Courtesy National Public Broadcasting Archives |

1961 |

|

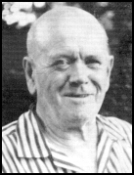

Immediately upon taking off he hears Howard B. Peck at the Manhattan Beach ground station calling him. After a minute or so gaining an altitude of 500 feet Pickerill calls the ground station and reports to Peck the receipt of his signals loud and clear above the engine noise, no ignition shielding then being in use. The ground station also reports the receipt of clear signals from Pickerill in the air. Other signals are heard by Pickerill from steamships in the harbor of New York and from Marconi stations at Seagate and Sagaponack, L. I. The antenna on the plane consists of one wire hanging from one wing tip with a ground wire or counterpoise of equal length, 200 feet, hanging from the other wing-tip. The transmitter operated by the pilot consists of a two-inch spark coil with a mechanical interrupter, a condenser, adjustable spark gap, tuning inductance, hand key and a battery of six dry cells for power, a weight of 11 pounds, minus batteries. The receiving set comprises two different receivers, one a carborundum crystal and a tuning coil; the other an electrolytic detector using a glass-covered platinum wire with one end exposed in a potash solution, together with a potentiometer and three flashlight dry cell batteries and a tuning coil, total weight 5 pounds. The apparatus is mounted on the wing spar and strut adjacent the seat. The transmitting key is clamped around the pilot's right knee by means of a spring and the head phones are placed inside the helmet. An auxiliary key in the form of a push-button is clamped on the control lever. The ground equipment consists of a similar receiver and transmitter, mounted in a steamer trunk, with a collapsible mast and six-wire antenna. Messages are sent to the portable ground station; :I hear your signals good and loud, how do you get mine?" Reply received from portable ground station at Manhattan Beach; "Your signals are very clear and steady here. We are looking for you in air and will flash you as soon as we sight plane. Congratulations and safe landing." Continuous two way conversation is maintained after exchange of these two messages for the remainder of flight. Pilot Pickerill learned to fly in 1910, at Mineola, L. I., N. Y., but never bothered to obtain the FAI certificate. At the time of this demonstration he is in charge of the station of the United Wireless Telegraph Company on the roof-garden of the Waldorf-Astoria hotel. He remains in the employ of the company until 1912 when he joins the American Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company. In 1917 Pickerill becomes civilian flight instructor for the Aviation Section, Signal Corps, and is later commissioned. He then serves as instructor in radio and gunnery at Ellington Field and later with the late C. C. Culver at Gerstner Field in air-radio research. He is C.O. of the 135th Observation Squadron at Post Field, Fort Sill, and is assigned to special duty as instructor at the General staff College, Fort Leavenworth, in 1920, resigning September 22, 1920. On October 1, he joins the Radio Corporation of America and when RCA establishes its aeronautic division in 1928 to develop and manufacture radio apparatus of all kinds for the new air transport industry, Pickerill is placed in charge and he pilots a 8-place Fokker Super-universal in its tests over the intervening years to 1933. He holds commercial radion operator's license No. 1 and the special 1911 "pink" ticket which represents extra first-class commercial radio operator license. In 1950 he still holds an up-to-date commercial pilot's license and Radio-telegraph Operator and Radio-telephone Operator licenses---(Relay RCA house organ); interview with Pickerill by H. Cressy, of Bendix Radio Engineer, Sept. 20, 1944; letter RCA to E. L. J., Feb. 27, 1950; AF photos, AC 28827, 28827A, 28827B courtesy of Steve Remington - CollectAir |

|

Career of E. N. Pickerill, Pilot of the R. C. A., Combines Adventures of Sea and Air. He began flying in 1910, was a squadron commander in the air service during the war, became chief radio operator of the Leviathan when that ship first sailed under its new name and finally returned again to commercial aviation. With the United States entrance into the World War he joined the Army Air Service and was placed in command of the 135 Aero Squadron at Fort Sill, Okla., commanding also several other squadrons until the signing of the armistice. After several years of service he left the Leviathan staff to become an assistant superintendent of the R.C.A., and in July, 1928, organized the aviation division of the company. April 3, 1930 |

|

|

Circa 1928? Collection of Rick Bjorklund - 10-25-03 |

|

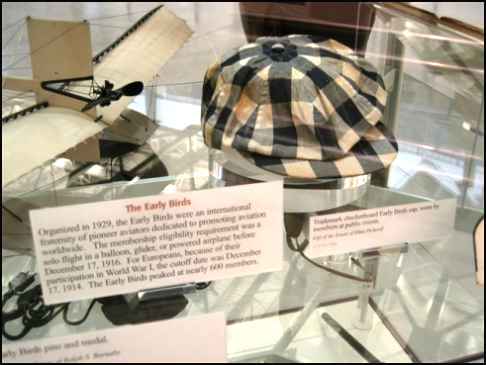

by Lee David Hamilton from AIRWORLD, September, 1966 Through The Early Birds the embryonic adventure of aviation's first decade grew to manhood. In the growing-up years that followed World War I, their efforts in old fashioned energy and newfangled engineering led to today's unlimited horizons of aircraft invention and design. This month the aviation pioneers will hold their once-a-year wingding in Los Angeles, a community embarrassingly barren of early aviation history. However, the Golden State itself, is a potpourri of early air history, home now to nearly 60 of the "old chirps," an irrestible magnet for senior citizens. The organization's charter dates from 1928 when English-born U.S. aviation pioneer P.G.B. Morriss (1884-1944) helped form the group, with the aid of a dozen friends. Any person who flew solo in a glider or machine' powered craft before December 17, 1916--and could prove it--was accepted in The Early Birds of Aviation, Inc. The cutoff date of 12/17/16 was selected, for at that time Federal authorities began team training of World War I pilots. After that, "aeroplanes" were no longer the private domain of aerobatic daredevils. Although the club's purpose was fellowship and hopefully the preservation of personal memorabilia., few members joined the ranks without a witness or two to their solo flight. "Bud" Morriss for example, earned his wings in St. Louis at the Benoist Flying School during the summer of 1912. Later he sold flying boats for the firm. While the exact number of early pioneers will never be known, an Early Bird memorial plaque presented to the Smithsonian Institution lists 567 men and women who soared their way to fame or, an early grave. The presentation was made only after years of arduous documentation by Elmo Neale Pickerill, Mineola, New York, secretary of the group. And those who never joined? Mr. Pickerill, now 81 and still an outstanding authority on U.S. pre-Lindbergh aviation history, believes no more than 675 persons flew solo during the first 13 years of powered flight. While The Early Birds made every reasonable effort to contact each aviatrix and aviator of the December, 1903-1916 era, it was never possible to reach them all. A hundred or so, as the old timers say, "had gone with the wind." One such "lost bird" was James Clifford Turpin (1886-1966), an exhibition pilot "discovered" living on Cape Cod. He joined The Early Birds only in 1961, having never heard of the group before, unaware that anyone might be interested in his contributions to a bygone time and place. Turpin, who soloed in 1910, was one of the earlierst pilots to fly for the Wright Brothers. There are, in fact, only two survivors--one civilian, one military--of not more than a dozen men who the Wrights personally taught to fly their machines. Elmo Pickerill, tutored by Orville, soloed on June 10, 1910. Major Benjamin D. Foulois, 86, of Washington, D. C., soloed in 1909--after only three hours of ground lessons. Many people believe the Wright boys taught a small army of men to fly. Not so, says "Pike," a name Elmo's dearest friends are permitted to use. The brothers established a number of Wright Brothers Flying Schools along the Eastern and Gulf coasts, which in turn, trained about 115 pilots, the exact number being lost to history. Eight weeks after his solo, Elmo Pickerill made world headlines when he became the first person to send and receive radio communications between an airplane and Earth. The historic event took place on August 4, above Mineola and Manhattan Beach, Long Island, New York. Pickerill, a pioneer telegrapher, companion of Dr. Lee de Forest, and operator of a wireless shack on the old Waldorf-Astoria's roof garden, hooked up a suitable transmitter and receiver on his Wright Model "B." From his past experiences Pickerill knew that while flying both hands would be more than busy, so he developed a push-button telegraph key mounted on the right hand control lever, which he operated with his thumb. A portable ground station was set on a sandy beach, and as the frail "B" caught the wind, the world's first aircraft radio message was born. In the growing-up years of aviation all the young go-getters built their own craft. William C. Diehl, 75, of North Bergen, New Jersey, considered by many to be one of America's greatest flying instructors, constructed his first unbelievable air jalopy in 1913, soloed the following year. As test pilot, daredevil, and commercial flyboy from1914 to 1962, he had logged "for the record," 6,300 hours behind the "stick," and so many thousand more hours as teacher that he has lost count. Bill pioneered team teaching techniques as a civilian flying instructor during World War I, and in the past 40 years has taught more than 5,000 men and women to fly. He operated one of the world's first air taxi services (1919), flew Pearl White for her "Perils of Pauline," was far famed for his stunt flying, and is even today a busy inventor of aviation and automobile devices. What is so remarkable about so many of today's Early Birds is their continuing activity in the business world, both within the field of aeronautics and outside its perimeter. Grover Cleveland Loening who flew solo in a flying boat of his own design, first took off from Raritan Bay, New Yoirk on July 17, 1912. The Wright Brothers' first Chief Engineer, he later became a founder and president (1928-1938) of the Loening Amphibian Company, and provided financial assistance to the founders of Grumman Aircraft Engineering Co. At 17, Harry A. Bruno soloed in a glider of his own design the day after Christmas, 1910, more than half a century ago. Few men can claim association with as manyh world renowned aviation events as this 73-year-old New York public relations consultant who helped tell the story of Richard Byrd's 1926 North Pole flight, Lindbgergh's epic voyage of 1927, and the Graf Zeppelin record of 1928. On the eve of the SSST, Harry Bruno concerns himself with an international jet airline, helicopter commuter services, and the aerospace industry. Stanley Hiller zoomed through the clouds on a warm June day in 1911, at Alameda, California, in a plane and engine of his own design. The delicate craft--it looked like a flying T-square--was kept aloft with a six cylinder, 30 horsepower motor. In the years that followed the aviator-engineer with his Hiller Hydroplanes became a common sight on the waters of Alameda's San Leandro Bay and Oakland's Lake Merritt. As if to prove little chips do come from old blocks, Stanley Hiller, Jr., invented his own helicopter shortly before his 18th birthday, with a little help from Dad. Today, Hiller Helicopters roll off the assembly line, and Stanley Sr., keeps up an independent schedule as a consulting engineer. The now ancient flying boats held a common tie for many of the Early Birds. Eighty-year-old Bertell W. King (of Seven Day Bike Race fame) flew his first--a Curtiss--off St. Augustine Fla., in June, 1913. King's business is now the measurement of bulk cargoes for water carriers and his most recent patent was granted only last year. During World War II he offerred his hydrofoil design to the U. S. Navy. A prophet before his time, the devie was turned down with a polite thanks-but-no-thanks. Earlier this year, after four decades of service with the aviation products division of Phillips Petroleum, Will D. Parker retired (well, not really!) to Sedona, Arizona. At 72, "Billy" has more than 18,000 hours in all types of planes, from modern jets to the go-for-glory bird he invented on his own, back in his 1912 high school days in Colorado. As an aircraft builder he sold 10 planes of his own design to other pilots, keeping two pusher (prop facing rearward) models as personal heirlooms. During the past two generations these two pushers have flown everywhere in the U.S., and Billy has pleased more millions from the squeaky wicker seats of these antiques than he has time to recount in memories. A past president of The Early Birds, he is now in the process of assembling his vast historical collection for presentation to the Smithsonian National Air Museum, whose Head Curator & Historian is Paul Garber, and Early Bird, of course. What The Early Birds of Aviation will do in Los Angeles from October 13-16, 1966, is what they love most: talk, talk, talk, about you know what. Early Bird Number One, as he is fondly ........ |

|

|

Worn by Members at Public Events Gift of the Estate of Elmo Pickerill EARLY BIRDS Photo courtesy of Ross Levin, owner Aviation Art Hangar |

|

He died in 1968 From The Early Birds of Aviation Roster of Members, 1996 and from Kevin Phillips, his 1st Cousin, three times removed. |

|